This section covers the most fundamental concepts of using R. Intermediate concepts are covered in intermediateConcepts and advanced concepts are covered in advancedConcepts. Use the beginnerTest exercises to test your mastery of the concepts introduced in this tutorial.

If you are working through this tutorial as part of the Geoscience 541: Paleobiology course, you must do the beginnerTest exercise and hand in your answers at the start of the next lab period.

- The most basic R concepts

- Why should you use R?

- R as a fancy scientific calculator

- Using functions for basic math

- Storing data in an array

- The different types of data

- Vectors and matrices as special arrays

- Referencing elements of an array

- Multiple data types in an array

- On the proper names of things

Throughout this tutorial there will be references to objects and functions. These are the two fundamental units of the R programming language. R stores information as objects and uses functions to interact with the objects. The following quote (not mine) summarizes the relationship quite well.

“Everything that exists in R is an object. Everything that you do in R is a function.”

The line between objects and functions can become somewhat blurred because all functions are stored as objects and all objects can only be interacted with via functions. Don't be discouraged by this complexity, just remember the above quote and you will be fine.

If you are ever feeling overwhelmed by what you are learning or doing in R, never forget that everything you do in R is just a function designed for one of the following four purposes. Determine which step you are trying to perform, and proceed from there.

- Mathematical Operations - Using R as a glorified calculator

- Storing Data - Storing data in a format that allows you to perform a mathematical operation on it.

- Reshaping Data - Changing the format of previously stored data so you can perform a different kind of operation on it.

- Visualize Data - Methods to make graphs or other visual representations of stored data.

Although there are literally thousands of R functions, so long as you know a handful of basic methods for each of these four steps you can accomplish anything. This beginner's tutorial will largely focus on Mathematical Operations and Storing Data.

"Always talk about R!"

Spell things out for future readers of your programs as explicitly as possible – especially for me, because I’m grading you! You want other programmers to easily recognize what you are trying to accomplish with a particular line of code. A quote that I quite like is:

"Always annotate your code, because the sucker trying to figure what you did six months from now is going to be you."

To do this you should always leave thorough comments in your code. Comments in R are always preceded by the # symbol. Anything that follows a # symbol will not be executed by the software.

> # 2 * 5; everything on this line is a comment none of this will execute if you copy it into R

> 2 * 5 # comments can be placed after an expression. Whatever is in front of the # WILL execute.

[1] 10

"The computer is always right."

As a beginner, you will often encounter errors. It is easy to become frustrated when the computer does not do what you want. However, remember that the computer "'tis naught but clockwork" and can only do what you tell it to do. If you are getting an error, it is almost certainly your fault. Don't despair and don't get mad. Take a deep breath, think about what you are trying to do, and try again.

If you have ever used a scientific or graphing calculator, then you already intuitively know all the basics of doing arithmetic in R. Yay, you've learned about 25% of R without doing anything! But, let's just start with a quick review anyway.

# Addition

> 2+2

[1] 4

# Subtraction

> 5-3

[1] 2

# Multiplication

> 3*4

[1] 12

# Division

> 1/5

[1] 0.2

# Exponents

> 10^2

[1] 100

# Modulus (i.e., the remainder)

> 4 %% 2

[1] 0

# Make sure you always pay attention to the order of operations (i.e., PEMDAS). Compare the following two

# expressions.

> (1+3)/(5/6)

[1] 4.8

> 1+3/5/6

[1] 1.1

# Also, be careful about those tricksy negative signs!

> -5^2

[1] -25

> (-5)^2

[1] 25

You can also perform what are called logical operations. A logical returns a value of either TRUE or FALSE. Logicals are extraordinarily important in R.

# Let's ask R if 1 is greater than 0

> 0 > 1

[1] FALSE

# What about if 5 is 1/2 of 10?

> 5 == (1/2 * 10)

[1] TRUE

Notice that we used == to ask if these two quantities are equal, rather than a single = sign. Most operators in R are straightforward, but there are some - e.g., == - that are not intuitive.. Here is a list of the basics. There are a few other operators in R, but we will worry about them later.

| Operator Example | Operator Definition |

|---|---|

| x > y | Is x greater than y |

| x >= y | Is x greter than or equal to y |

| x < y | Is x less than y |

| x <= y | Is x less than or equal to y |

| x == y | Is x equal to y |

| x != y | Is x not equal to y |

Of course, writing out the arithmetic every time wouldn't be any better than just using a calculator. The first benefit that R has over a calculator is it has many functions for arithmetic expressions that you can use as shortcuts.

# For example, if I wanted to take the square root of a number. I could just write out the expression.

> 4^(1/2)

[1] 2

# But, I can use the sqrt() function to do this as well. Note that all functions have two parts.

# The function name - e.g., sqrt - and a set of function arguments. Arguments are objects that you want

# the function to evaluate - e.g., the number 4. Function arguments are always placed in

# parentheses.

> sqrt(4)

[1] 2

Now you might be thinking, that doesn't really save any time compared to writing out the expression. True, but functions will save you time on more complex expressions.

# Let's try typing out 10!

> 10*9*8*7*6*5*4*3*2*1

[1] 3628800

# Versus using the factorial function

> factorial(10) # much clearer!

[1] 3628800

The second most important benefit of functions is that they explicitly say what your code is doing - remember the first rule of R! Seeing factorial(10) makes it immediately obvious that you are calculating the factorial of ten.

These simple functions probably still don't seem that impressive if you consider that most calculators already have buttons for square roots, factorials, and the like. However, functions in R don't really shine until they are paired with stored data.

Let's consider a quadratic equation, 5x^2+3x+7. Let's say we want to solve this equation for x=4 that's easy to do in the way we've already learned.

# 5x^2+3x+7, where x=4

> 5*(4^2)+(3*4)+7

[1] 99

# But what if we want to solve this equation for multiple values of x? Let's try solving for x = 1,2,3, and 4.

# We can do this by telling R to perform the function on all four numbers at once using the c() command.

# The c() function tells R to treat the values inside the parentheses, separated by commas, as a single object.

> 5*c(1,2,3,4)^2+3*c(1,2,3,4)+7

[1] 15 33 61 99

# But what if we had a very long equation and/or a very long list of x values we want solve for? Typing out

# all of the x values with c() every time x appears in the equation could get very hard to read very quickly.

> 9*c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10)^3+6*c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10)^2+8*c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10)+2

[1] 25 114 323 706 1317 2210 3439 5058 7121 9682

A better alternative involves learning how to store data as an object, and then plug the object into equations. The most fundamental type of data object in computer science is generally called an array. In R, there is an even more fundamental type of data object known as a vector. For now, let's talk about arrays.

An array is essentially a set of values saved to your computer memory that is referenced by a name.

# Here's an example of how to make an array named "MyArray"

> MyArray<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=4)

# Once we've made the array named MyArray, then typing MyArray will return the values in the array.

> MyArray

[1] 1 2 3 4

# Similarly performing arithmetic on MyArray will apply that expression to all elements in MyArray

> MyArray+4

[1] 5 6 7 9

# You can input MyArray into a function, and the function will be applied to each element (number) in the array

> factorial(MyArray)

[1] 1 2 6 24

> 5*MyArray^2+3*MyArray+7

[1] 15 33 61 99

Remember that everything that exists in R is an object and everything that you do is a function. In the above example, MyArray is an object (specifically an array) that you created with the function array( ).

If you are ever interested in knowing whether an object is an array or a function, you can use the function class( ). All objects have a class.

> MyArray<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=4)

> class(MyArray)

[1] "array"

> class(array)

[1] "function"

Any time that you want to store the output of a function as an object, you use the <- operator, also known as the assign operator. In the MyArray example, <- tells R to store the output of the function on the right, array( ), under the name on the left - i.e., MyArray.

# Here are some other examples

> FirstObject <- sqrt(5)

> FirstObject

[1] 2.236068

# Note that an existing object can be used to make a new object.

> SecondObject <- factorial(FirstObject^2)

> SecondObject

[1] 120

Let's talk some more about the array( ) function, and functions in general. Aside from the symbolic operations described above (e.g., +, -, /, >, !=, etc.), functions follow a simple format. They have a name (e.g., sqrt, factorial, array) that is followed by parentheses. Within these parentheses you place one or more arguments that tell the function what to do.

# Let's review the "MyArray" example again

> MyArray<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=4)

The data= is your way of telling it what data you want stored in the array. In this case, the numbers one, two, three, and four, but you could substitute any list of values or even a single value.

# Single value example

> SingleArray<-array(data=5,dim=1)

In other words data is the argument name, and you're telling it what values you want that argument to take. Another way of thinking about this is that you're telling R to temporarily create an object named data that the function array( ) should use and then delete once the function completes.

Similarly, dim= (short for dimensions) indicates how many values you want in the array. If you indicate more values to the array then you provide, R will simply repeat the values you did give it until the array is full.

> MyArray<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4,5),dim=10)

> MyArray

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

Beware! This is a really bad behavior that most computer languages would not allow. The potential for introducing error into your calculation in this way isn't trivial, so be precise when defining your array size!

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of dim= is that you can also give it multiple values. Remember that when we want to treat multiple values as a single object we use the c( ) function.

# Two dimensional array

> TwoArray<-array(data=c(0,1),dim=c(4,6))

> TwoArray

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[4,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

Eseentialy, you told R to make 6 arrays with 4 values and store them within a single object named TwoArray.

# You can do this as many times as you'd like. For example, 2 sets of 6 sets of arrays with 4 values.

> ThreeArray<-array(data=c(0,1),dim=c(4,6,2))

> ThreeArray

, , 1

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[4,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

, , 2

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[4,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

We therefore describe arrays based on the number of arrays referenced within them. A single array is a 1-dimensional array. An array of arrays is a 2-dimensional array. An array of arrays of arrays is a 3-dimensional array, and so forth.

Incidentally if you ever want to check the dimensions of an array, you can use the dim( ) function.

# Check the dim of MyArray

> dim(MyArray)

[1] 4 6 2

What if we want to store something other than a number? There are a variety of data types in R, but there are only a few that you really need to know. Let's begin with the three most basic types.

| Data Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| logical | TRUE or FALSE |

| character | Letters, numbers, and symbols that act like letters |

| numeric | Numbers that act like numbers |

Type logical is fairly straightforward. It is simply a TRUE or a FALSE value. Note, however, that R will convert TRUE to 1 and FALSE to 0 if you try to perform basic mathematical operations on an array of logical data.

# Create an array of logical values

> MyLogical<-array(data=c(TRUE,TRUE,FALSE,TRUE,FALSE,TRUE),dim=6)

> MyLogical

[1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE

# Multiply your 1-dimensional array of logicals by 3

>MyLogical*3

[1] 3 3 0 3 0 3

# You can check what type of data you have using the typeof( ) function.

> typeof(MyLogical)

[1] "logical"

# Or if you have a specific guess you can use the is( ) function.

> is(MyLogical,"logical")

[1] TRUE

# If you want to see if ANY elements of your logical array are TRUE, use the any( ) function.

> any(MyLogical)

[1] TRUE

# IF you want to see if ALL elements of your logical array are TRUE, use the all( ) function.

> all(MyLogical)

[1] FALSE

Type character is also fairly straightforward. It is basicaly a way of "de-mathing" something. You tell R that something is meant to be a character by using quotation marks " ".

# Create an array of characters made of letters

> MyCharacters<-array(data=c("Bob","Loves","Lucy","Almost","As","Much","As","He","Loves","R"),dim=10)

> MyCharacters

[1] "Bob" "Loves" "Lucy" "Almost" "As" "Much" "As" "He" "Loves" "R"

# Check the type

> typeof(MyCharacters)

[1] "character"

By "de-mathing", I mean that R will reject any attempts to do math on your array of characters, even if those characters are numbers.

# Create a vector of numbers as characters

> MyCharacters<-array(c("1","2","3","4"),dim=4)

[1] "1" "2" "3" "4"

# Attempt to add these numbers together using the sum( ) function.

> sum(MyCharacters)

Error in sum(MyCharacters) : invalid 'type' (character) of argument

We need to use " " marks so that R know you are not referencing an object.

# Without " " marks returns an error because it thinks you are referncing an object.

> WithoutQuotes

Error: object 'WithoutQuotes' not found

# With " " marks returns a character string.

> "WithQuotes"

[1] "WithQuotes"

Type numeric is both a simple and complicated data type. Basically, numeric data are, you guessed it, numbers that you want to do math on.

# Create a numeric array

> MyNumeric<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=4)

# Attempt to add all numbers in MyNumeric together

> sum(MyNumeric)

[1] 10

# Check if MyNumeric is of type numeric

> is(MyNumeric,"numeric") # Remember the is( ) function from before?

[1] TRUE

# Check its data type

> typeof(MyNumeric)

[1] "double"

It gives double instead of numeric! There are actually a couple of types of numeric data. For our intents and purposes, however, we will just consider double to be synonymous with numeric and leave it there for now.

"Data! Data! Data! I cannot add letters together."

As you progress with R you will learn that keeping track of what type of data you are using becomes increasingly important. Most errors that beginners and intermediate useRs encounter are, on some level, a result of using the wrong data type. Therefore, one of the first things you should do when you get an error is double check that you are using the right type of data.

This is worth doing even if you are sure that you entered the data correctly. This is because some R functions will coerce (convert) your array from one data type into another without your realizing it. In most cases, this is actually a very convenient feature of R, but in other cases it can be the source of much frustration.

The majority of work done in R is either 1- or 2-dimensional. This has led to the emergence of shorthand terms. A vector is a one-dimensional array and a matrix is a two-dimensional array. The overwhelming majority of R users exclusively use the vector and matrix terminology rather than n-dimensional array terminology. Importantly, not only is there a difference in terminology, there are actually separate functions, for convenience, that specifically use these terms.

# Compare a 2-dimensional array

> x<-array(data=c(0,1),dim=c(4,6))

> x

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[4,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

# With a Matrix. Notice that matrix( ) doesn't take a single dim= argument,

# but rather has separate arguments for the number of rows (nrow) and columns (ncol)

> y<-matrix(data=c(0,1),nrow=4,ncol=6)

> y

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[2,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

[3,] 0 0 0 0 0 0

[4,] 1 1 1 1 1 1

# We can check if these two objects are identical with the identical() function.

> identical(x,y)

[1] TRUE

# Or we can use the "**==**" operator

> x == y

[1] TRUE

# Based on what you've seen above, you may think that you have deduced the appropriate

# pattern for writing out a vector.

> z<-vector(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=4)

Error in vector(data = c(1, 2, 3, 4), dim = 4) :

unused arguments (data = c(1, 2, 3, 4), dim = 4)

Nope, doesn't work! Even though vectors are conceptually identical to a 1-dimensional array, they are not operationally identical. Instead, you make a vector by using the c( ) function we've been using all along.

# Make a vector

> MyVector<-c(1,2,3,4)

> MyVector

[1] 1 2 3 4

# Let's make a 1-dimensional array.

> MyArray<-array(c(1,2,3,4),4)

> MyArray

[1] 1 2 3 4

# You can what type of array something is by using the is()

> is(MyVector,"vector")

[1] TRUE

# Let's test if the 1-D array, MyArray, is identical with the previous vector, MyVector.

> identical(MyVector,MyArray)

[1] FALSE

# Similarly, dim( ) will not work on a vector.

> dim(MyVector)

NULL

# You have to use the special function length( )

>length(MyVector)

[1] 4

If you look carefully at how we define arrays, you will notice that we need to first create a vector using the function c( ) - e.g., MyArray<-array(**c(1,2,3,4)**,4). Generally, vectors are used more often than 1-dimensional arrays because vectors are more fundamental. So, fair warning, be careful as to whether you are using vectors, matrices, or arrays.

Each array is made up of a set of values. Each value within an array is known as an element.

# Create a simple array with the array( ) function.

> MyArray<-array(data=c(5,6,7,8,9,10),dim=6)

> MyArray

[1] 5 6 7 8 9 10

In the above example, MyArray has six elements, the numbers 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. If you want to reference a specific element within the array, you use single brackets around the index or position of the element.

# Refernce the 6th element of MyArray

> MyArray[6]

[1] 10

# Reference the 3rd element of MyArray

> MyArray[3]

[1] 7

You can also name the various elements within an array. You can do this (1) when the array is first created, or (2) after you've already created the array. For now, let's just add names to an existing array.

# Add names to an existing array using the names function.

> MyArray<-array(data=c(5,6,7,8,9,10),dim=6)

# Let's check the names of MyArray using the names( ) function.

> names(MyArray)

NULL

Notice that there are no names attached to this array yet, so it returns an empty array - i.e., NULL.

# You can store an array of names (as a character data type) to this empty array.

> names(MyArray)<-c("First","Second","Third","Fourth","Fifth","Sixth")

> MyArray

First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth

5 6 7 8 9 10

# You can now access an element based on its **name**, rather than its **index** or **position**

# Find the fifth element.

> MyArray["Fifth"]

Fifth

9

What about those commas we saw before in the 2 and 3-dimensional array examples? The commas are used to separate out which dimension you are talking about. Here is an example.

# Let's make a 3-dimensional array, with 2 arrays of 6 arrays of 4 elements.

# Incidentally, notice that I'm going to use the ":" operator for the first time.

# The colon means to make a sequence of numbers ranging from x to y - e.g., 1:4 = 1,2,3,4.

> ThreeArray<-array(data=c(1:48),dim=c(4,6,2))

> ThreeArray

, , 1

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 1 5 9 13 17 21

[2,] 2 6 10 14 18 22

[3,] 3 7 11 15 19 23

[4,] 4 8 12 16 20 24

, , 2

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 25 29 33 37 41 45

[2,] 26 30 34 38 42 46

[3,] 27 31 35 39 43 47

[4,] 28 32 36 40 44 48

# Let's say that we want to find element 43

# 43 is in the 3rd row of the 5th column of matrix number 2.

> ThreeArray[3,5,2]

[1] 43

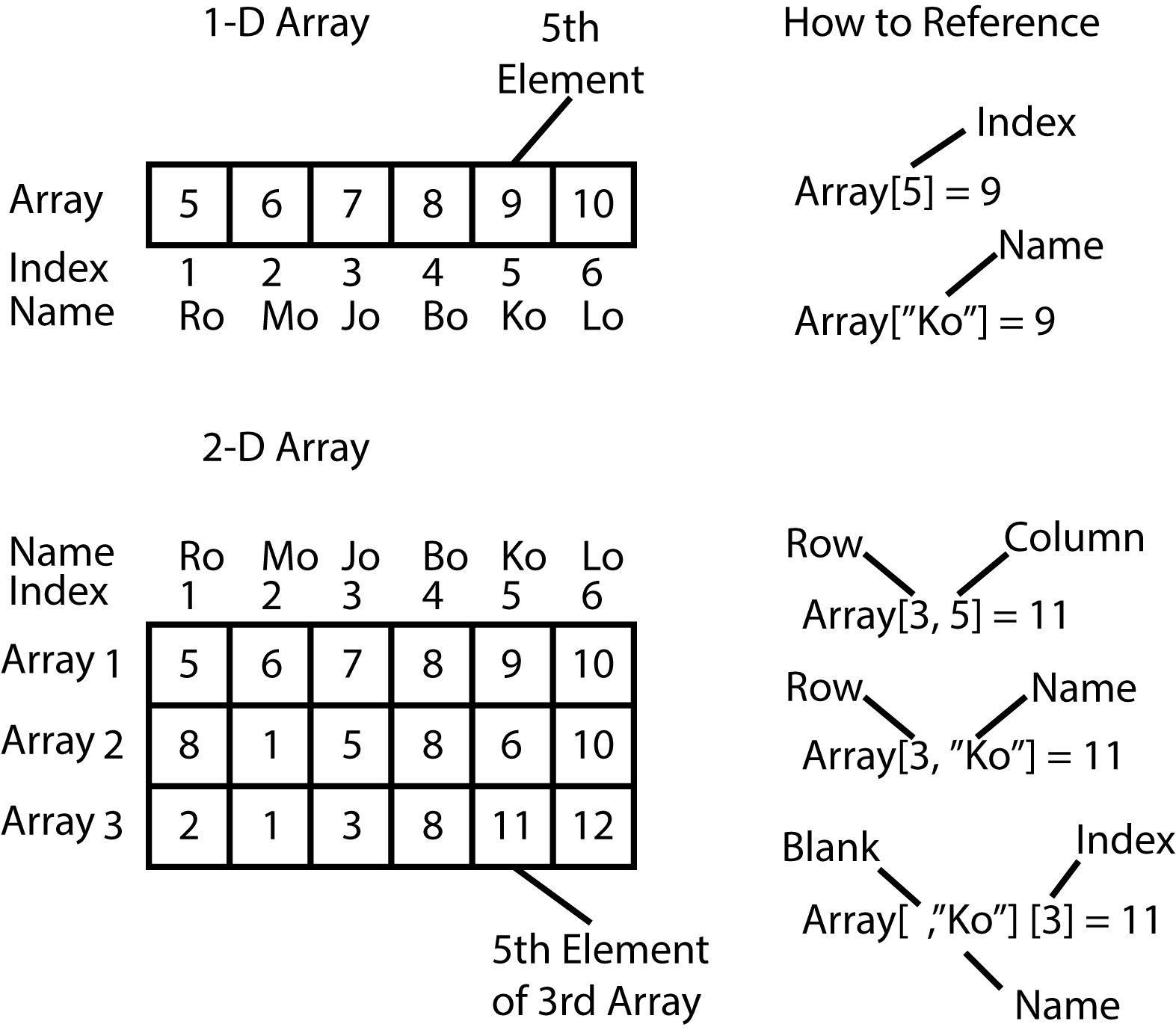

The figure below depicts several other ways you can reference the elements within an array using bracket notation. Bracket notation, by the way, is known in R as subscripting. If you get an error that mentions subscripts then you know you used the wrong index when attempting to reference one or more elements of an array. This is a very common source of error, don't be discouraged if you get a lot of them when you're first starting out.

"R uses arrays too. Take advantage!"

You may have noticed that throughout this tutorial R generally prefaces its answers to our questions with [1]. That is its way of telling you that its response is the first element of an array - i.e., the invisible answer array. Because its answer is an array you can also subscript the answer.

> ThreeArray<-array(data=c(1:48),dim=c(4,6,2))

# Find the dimensions of our new three dimensional array

> dim(ThreeArray)

[1] 4 6 2

# What if we just want to know the number of columns?

# You can subscript the output of dim( ) since it is also an array.

> dim(ThreeArray)[2]

[1] 6

An important property of arrays is that they will only allow you to store one type of data within them. For example, let's try to make a vector with both characters, logicals, and numbers.

# My multi-datatype array

> MultiArray<-c(TRUE,1,2,3,4,"Bob")

> MultiArray

[1] "TRUE" "1" "2" "3" "4" "Bob"

# Check to see the data type

> typeof(MultiArray)

[1] "character"

Notice that R simply coerced everything to type character. This is R's default behavior when you mix data types. If you want to store multiple types of data in a single object you are going to have to use a special type of array known as a list. Lists are created using the list( ) function.

Lists are the most versatile form of data object. You can store multiple types of data in a variety of formats within a single list. You can even get fancy and have lists of lists. This is both a boon and an a bane, because this versatility makes them much more complex and difficult to use. Let's try to make MultiArray again using list( ).

# My multi-datatype array

> MultiList<-list(TRUE,1,2,3,4,"Bob")

> MultiList

[[1]]

[1] TRUE

[[2]]

[1] 1

[[3]]

[1] 2

[[4]]

[1] 3

[[5]]

[1] 4

[[6]]

[1] "Bob"

Although this output seems a bit cluttered and confusing with all of the extra brackets, it is actually very straightforward.

All arrays are ultimately one-dimensional arrays (i.e., vectors) - in fact, properly speaking, there is no other kind of array in R or any computer language. We simulate two (or more) dimensional arrays by creating a one dimensional array whose elements are also arrays. There can be as many arrays nested within arrays as you want - e.g., a four dimensional array is an array of arrays of arrays of arrays.

Lists are just more explicit about this relationship than standard arrays. Let's try and illustrate this relationship with an example.

# Create a 2-dimensional array of characters.

> MyCharacter<-array(c("a","b","c","d","e"),dim=c(5,5))

> MyCharacter

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

[1,] "a" "a" "a" "a" "a"

[2,] "b" "b" "b" "b" "b"

[3,] "c" "c" "c" "c" "c"

[4,] "d" "d" "d" "d" "d"

[5,] "e" "e" "e" "e" "e"

# Create a 1-dimensional array of logicals

> MyLogicals<-array(c(TRUE,FALSE),dim=10)

> MyLogicals

[1] TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE

# Create a 2-dimensional array of numerics

> MyNumerics<-array(c(1,2,3,4,5),dim=c(3,4))

> MyNumerics

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 4 2 5

[2,] 2 5 3 1

[3,] 3 1 4 2

# Bind each of these arrays together in a list.

> MyList<-list(MyCharacter,MyLogicals,MyNumerics)

> MyList

[[1]]

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

[1,] "a" "a" "a" "a" "a"

[2,] "b" "b" "b" "b" "b"

[3,] "c" "c" "c" "c" "c"

[4,] "d" "d" "d" "d" "d"

[5,] "e" "e" "e" "e" "e"

[[2]]

[1] TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[[3]]

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 1 4 2 5

[2,] 2 5 3 1

[3,] 3 1 4 2

Presumably you can deduce from the output of MyList what the [[ ]] mean. Just as single [ ] identify an element within an array, the [[ ]] identify an object within a list - usually another type of array.

# Find the first array in MyList

> MyList[[1]]

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

[1,] "a" "a" "a" "a" "a"

[2,] "b" "b" "b" "b" "b"

[3,] "c" "c" "c" "c" "c"

[4,] "d" "d" "d" "d" "d"

[5,] "e" "e" "e" "e" "e"

# See if it is identical to MyCharacter

> identical(MyList[[1]],MyCharacter)

[1] TRUE

# Access row 1, column 2 of the MyNumeric array in MyList

> MyList[[3]] [1,2]

[1] 4

You might think that you should use lists for everything since they are so flexible. However, as you may have noticed in the above examples, their output can be quite complex. Remember the first rule of R, clarity is king. Complex lists should be avoided whenever a simple array will suffice. Lists are also substantially slower in terms of computation.

In addition to lists and arrays, there is a special kind of hybrid between 2-dimensional arrays (matrices) and lists known as a data frame (often written as data.frame). Data frames maintain the same structure as a two-dimensional array (matrix), but they allow you to have different types of data in each column like a list.

Data frames are extremely desirable for data science. Imagine a clinical trial where you want to know the relationship between multiple variables. Some of the variables you want to keep track of might be best represented as numeric measurements (e.g., height, weight, age), logical measurements (e.g., TRUE = given real treatment, FALSE = given placebo), or character data (e.g., names, astrological sign).

The versatility to keep track of all of these different data types within a single array makes data frames the most popular class of data object in R.

# Make three different types of vector

> Weight<-c(85,110,75,70) # numeric

> Treatment<-c(TRUE,FALSE,TRUE,FALSE) # logical

> Sign<-c("Libra","Scorpio","Cancer","Libra") # Character

# Create a vector of subject names

> Subjects<-c("Bob","Lucy","Tina","Joe")

# Combine them into a data frame

# Note that we also use the "row.names=" argument so that the vector Subjects becomes

# you guessed it, the row names.

> MyFrame<-data.frame(Weight,Treatment,Sign,row.names=Subjects)

Weight Treatment Sign

Bob 85 TRUE Libra

Lucy 110 FALSE Scorpio

Tina 75 TRUE Cancer

Joe 70 FALSE Libra

There are several limitations, or at least caveats, you should consider before you start using data.frames for everything. First, data frames, like all arrays, must be symmetrical.

# Make a vector of length 4

> Weight<-c(85,110,75,70) # numeric

# Make a vector of length 3

> Age<-c(20,21,32)

# Attempt to combine them into a data frame.

> MyFrame<-data.frame(Weight,Age)

Error in data.frame(Weight, Age) :

arguments imply differing number of rows: 4, 3

In other words, data frames will only accept a series of 1-dimensional arrays (vectors) of equal length. Only lists can be asymmetrical.

A second, lesser consideration, is that data frames are less computationaly efficient than matrices. Even something as simple as referencing a single element can be 10x slower on a data.frame than a matrix. However, since smaller matrices and data frames are so fast (nanoseconds) people rarely notice this difference. Nevertheless, because you never know if a Big Data worker might use one of your functions in the future, it is worth using matrices whenever possible.

The final consideration with data.frames is that they will, by default, convert your data of type character to type factor. Factors are one of R's best features, but will be covered in the advancedConcepts tutorial. For now, if you want to preserve your characters, you need to change the stringsAsFactors= argument of the data.frame( ) function to FALSE.

# Set stringsAsFactors= to FALSE in order to preserve characters as characters

> MyFrame<-data.frame(Weight,Treatment,Sign,row.names=Subjects,stringsAsFactors=FALSE)

Be very mindful of this behavior, it is a common source of frustration.

A few parting notes on the different types of data object. First, vectors, matrices, arrays, data.frames, and lists are the most common classes of data object, but there are a variety of other - more specialized - data objects out there. Some programmers will create custom data object classes that only work with their own functions. So don't panick if you run across some class that you've never heard of before.

Also, be warned that there are two different funtions for naming elements in a data object, depending on the class of the object. If you are naming elements in a vector or list you should use the names( ) function that we've already illustrated. If you are naming the elements in an array (including data.frames and matrices, of course), you will need to use the dimnames( ) function.

# Create a three dimensional array

> Delivered<-array(data=c(1,2,3,4),dim=c(3,3,2))

> Delivered

, , 1

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 4 3

[2,] 2 1 4

[3,] 3 2 1

, , 2

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 1 4

[2,] 3 2 1

[3,] 4 3 2

# If you want to rename the first dimension of the object.

> dimnames(Delivered)[[1]]<-c("Frank","Joe","Bob")

> Delivered

, , 1

[,1] [,2] [,3]

Frank 1 4 3

Joe 2 1 4

Bob 3 2 1

, , 2

[,1] [,2] [,3]

Frank 2 1 4

Joe 3 2 1

Bob 4 3 2

# If you want to rename second dimension of the object.

> dimnames(Delivered)[[2]]<-c("Pizzas","Burgers","Salads")

> Delivered

, , 1

Pizzas Burgers Salads

Frank 1 4 3

Joe 2 1 4

Bob 3 2 1

, , 2

Pizzas Burgers Salads

Frank 2 1 4

Joe 3 2 1

Bob 4 3 2

# If you want to rename the third dimension of the object

> dimnames(Delivered)[[3]]<-c("Monday","Tuesday")

> Delivered

, , Monday

Pizzas Burgers Salads

Frank 1 4 3

Joe 2 1 4

Bob 3 2 1

, , Tuesday

Pizzas Burgers Salads

Frank 2 1 4

Joe 3 2 1

Bob 4 3 2

Names are very powerful in R. Just by looking at the name of the array and its elements, you could make a reasonable guess that the array Delivered is a set of tables for how many Pizzas, Burgers, and Salads that Frank, Joe, and Bob delivered on Monday and Tuesday. Remember, conveying constant information to whoever is reading your code is the first and most important rule of R! Never forget!