This repository contains all the relevant material of a crowdsourced study that aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of five basic visualization types (Table, Line Chart, Bar Chart, Scatterplot, and Pie Chart) across 10 different visual analysis tasks and two different datasets (Cars and Movies). The goal is to help researchers to reproduce and build on our study.

We conducted this study to answer two main reserch questions:

Q1 How well are different tasks supported by each visualization? For example, what tasks can be performed well using a scatterplot?

Q2 Is there a correlation between user preferences and their performance time and accuracy when using different visualizations for each task?

Below are the types of questions we asked participants in our study. We determine these task types using the low-level task taxonomy proposed by Amar et al[1].

Retrieve Value. For this task, we asked participants to identify values of attributes for given data points. For example, what is the value of horsepower for the cars?

Filter. For given concrete conditions on data attribute values, we asked participants to find data points satisfying those conditions. For example, which car types have city miles per gallon ranging from 25 to 56?

Compute Derived Value. For a given set of data points, we asked participants to compute an aggregate value of those data points. For example, what is the sum of the budget for the action and the sci-fi movies?

Find Extremum. For this task, we asked participants to find data points having an extreme value of an data attribute. For example, what is the car with highest cylinders?

Sort. For a given set of data points, we asked participants to rank them according to a specific ordinal metric. For example, which of the following options contains the correct sequence of movie genres, if you were to put them in order from largest average gross value to lowest?

Determine Range. For a given set of data points and an attribute of interest, we asked participants to find the span of values within the set. For example, what is the range of car prices?

Characterize Distribution. For a given set of data points and an attribute of interest, we asked participants to identify the distribution of that attribute values over the set. For example, what percentage of the movie genres have a average gross value higher than 10 million?

Find Anomalies. We asked participants to identify any anomalies within a given set of data points with respect to a given relationship or expectation. We crafted these anomalies manually so that, once noticed, it would be straightforward to verify that the observed value was inconsistent with what would normally be present in the data (e.g., movies with zero or negative length would be considered abnormal). For example, which genre of movies appear to have abnormal length?

Find Clusters. For a given a set of data points, we asked participants to find clusters of similar data attribute values. For example, how many different genres are shown in the chart below?

Find Correlation. For a given set of two data attributes, we asked participants to determine if there is a correlation between them. To verify the responses to correlate tasks, we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) to ensure that there was an strong correlation (r ≤ −0.7 or r ≥ 0.7) between the two data attributes. For example, is there a strong correlation between average budget and movie rating?

In our experiment we used Cars and Movies datasets. Both datasets include data attributes of Nominal, Ordinal, and Numerical types. The Cars dataset provides details for 407 new cars and trucks for the year 2004. This dataset contains 18 data attributes describing each car. The Movies dataset provides details for 335 movies released from 2007 to 2012, and contains 13 data attributes.

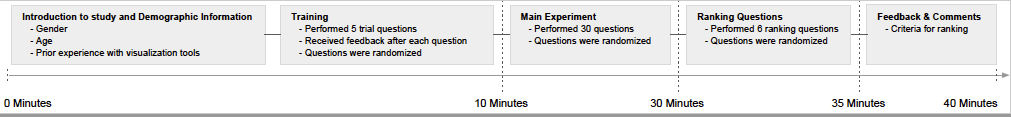

To address our research questions, we needed to test how the different visualization techniques affected the user performance time, accuracy, and preferences for different tasks.

To analyze the differences among the various visualizations, we first calculated separate mean performance values for all questions. That is, we averaged outcome values of questions for each visualization and task. Before testing, we checked that the collected data met the assumptions of appropriate statistical tests. The assumption of normality was not

satisfied for performance time.

However, the normality was satisfied for log transformed of time values. So, we treated log-transformed

values as our time measurements.

We conducted repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each task independently to test for differences among the various visualizations, datasets, and their interactions with one another. While Visualization had significant effects on both accuracy and time, Dataset had no significant effect on accuracy or time.

Bar Chart is the fastest and the most accurate visualization type. This result is inline with prior work on graphical perception showing that people can decode values encoded with length faster than other encodings such as angle or volume. Conversely, Line Chart has the lowest aggregate accuracy and speed. However, Line Chart is significantly more accurate than other charts for Correlation and Distribution tasks. This finding concurs with with earlier research reporting the effectiveness of line charts for trend finding tasks. Nonetheless, the overall low performance of Line Chart is surprising and, for some tasks, can be attributed to the fact that the axes values ("ticks") were drawn at intervals. This makes it difficult to precisely identify the value for a specific data point.

While Pie Chart is comparably as accurate and fast as Bar Chart and Table for Retrieve, Range, Order, Filter, Extremum, Derived and Cluster tasks, it is less accurate for Correlation, Anomalies and Distribution tasks. Pie Chart is the fastest visualization for performing Cluster task. High performance of Pie Chart for these tasks can be attributed to its relative effectiveness in conveying part-whole relations and facilitating proportional judgments, particularly when the number of data points visualized is small. Pie Chart may have been further helped by having colored slices with text labels showing the data values. Overall, Scatterplot performs reasonably well in terms of both accuracy and time. For the majority of tasks Scatterplot is among the most effective top three visualizations, and it was never the least accurate or slowest visualization for any of the tasks. One reason for this could be that people are very accurate and fast in perceiving “position”.

Table, Bar Chart, and Pie Chart are the fastest and the most accurate visualizations for performing Retrieve tasks. Successful performance of Retrieve tasks highly depends on readers ability to accurately identify the value for a certain data point. As prior work points out, tables are well-suited for retrieving the numerical value of a data point when a relatively small number of data points are displayed. While performing Retrieve task using Table is fast and accurate, performing Order, Extremum and Distribution tasks are relatively slow.

Overall, Bar Chart and Table are the two visualization types highly preferred by participants across most of the tasks. Bar Chart is always among two top-performing visualizations for almost all tasks, so this makes sense that people prefer using Bar Chart over other visualizations. Surprisingly, while performing some of the tasks (e.g., Distribution, Anomalies) using Table is relatively slow and less accurate, participants still prefer Table for performing these tasks. Familiarity of people with tables and easiness in understanding tables could have helped people to prefer using tables over other visualizations. To determine whether performance time and accuracy are related to user preferences, we calculated the correlation between performance time, accuracy, and user preference. We found a positive correlation between accuracy and user preference (Pearson’s r(5) = 0.68, p < 0.05), indicating people have a preference for visualizations that allow them to accurately complete a task. We also found a weak negative correlation between performance time and user preferences (Pearson’s r(5) = −0.43, p < 0.05).

This folder contians data collected from the experiment. All files are in the .xls format. In order to open each of them you need to have microsoft office Excel. If not you can just open them using Google sheet.

This folder contains all the analysis we ran to make sense of our data. If you have SPSS installed on your machine you can check the raw data using SPSS as well. We also provided results of the spss in pdf format. You should be able to read the results without requiring SPSS on your machine.

We believe results of our study has at least two important applications. First, our results can be used as series of theoretical guidelines to inform visualization designers and those new to data visualization. Second, as there is an increasing trend in automating the process of visualization design using visualization recommender systems, these results can be applied to advance processes of generating, filtering, and pruning the recommendations.

An important avenue for continued research is creating a recommendation engine that incorporates the findings of this study. In particular, we plan to design an engine that takes into account performance time, accuracy, and user preferences when suggesting visualizations. Once we have such an engine, we can use it to develop new visualization recommendation systems based on user-specified tasks and data attributes. One relevant application area of such a recommendation engine can be natural language interfaces for data visualization. In such interfaces people tend to specify tasks as a part of their questions (e.g., “Is there a correlation between price and width of cars in this dataset?”). The engine can be used to leverage this knowledge to suggest more effective visualizations for a given query. Another category of systems that might benefit from such an engine are behavior-driven recommendation systems. Such systems often extract analytical tasks from user interactions. These extracted tasks can be used as input to the engine for these systems to suggest more effective visualizations. All these applications would also benefit from models trained on the results of the current study (or any other empirical performance data) that can predict the task performance of “unseen" visualizations

[1]. Robert Amar, James Eagan, and John Stasko. 2005. Low-level components of analytic activity in information visualization. In Information Visualization, 2005. INFOVIS 2005. IEEE Symposium on. IEEE, 111–117.